Wednesday, January 6, 2010

Over the Hills and Far Away...

Sunday, April 19, 2009

Over the Hills and Far Away...

We'll continue our tour of the Case Study Homes, beginning with Pierre Koenig's Case Study #21 @ 3098 Wonderland Park Ave, other wise known as the Bailey House, moving east to see Rodney Walker's Case Study #17 @ 7861 Woodrow Wilson Drive, and finish off with Case Study #1 by J.R. Davidson @ 10152 Toluca Lake Ave. We'll meet up at the Starbucks thats in the shopping mall at the base of N. Crescent Heights Blvd & Sunset Blvd (8044 W. Sunset Blvd, Los Angeles, CA) @ 10am and figure to head out by 10:30. We'll be taking Laurel Canyon up to Case Study #21, so remember your helmets/water/energy bars because the climb up to mullholland is rough. We'll take mulholland over to Woodrow Wilson to see CSH #17, then take Woodrow Wilson down to the 101, cross over the bridge over the 101, take E Cahuenga north to Barnham Blvd to Lakeside Drive and finally to Toluca Lake Ave. Given the terrain, we'll probably stop for lunch in Universal City or somewhere near by before heading over to CSH #1.

Thursday, April 2, 2009

The Nature of Forces...

Structural Rationalism, minimalism, mid century modern, call it what you want, but Pierre Koenig's work stands alone as one of the truly great innovators and timeless masters of architecture and architectural theory. Koenig's own personal theory on architecture, as a discipline which is driven by and at the service of its context, manifested in what he called the 'Nature of Forces' laboratory (which was also a studio he taught @ USC) broke architectural design down to its most primitive elements, and showed us the power of not being in order to be. The constraints and opportunities of the site dictates a clear diagram and that diagram is immediately manifest in structure and space. Architecture is about the way we live, and life is an extension of our relationship with nature, so why not remove as much of the 'architecture' from the equation as we can so that we can cut to the chase and enjoy life?

We started with a not so typical beach house which fits Koenig's theory to the 't'. Perched on the upward sloping side of a street in the Palisades, the Schwartz House is lifted up from its siting and torqued to find the best views of the Pacific. Though not as warm feeling as the white painted steel and glass which typified is socal creations, the power of its logical expression is immediately recognizable and certainly sets it apart from its surroundings. Next we stopped off at Koenig's own residence in Brentwood to check out his own version of a stepped hillside retreat (albeit on a flat parcel of land) for the sake of opening interior space out into courtyards and gardens. His wife Gloria still resides in the house, and if you're lucky enough to catch up with her, she'll gladly talk to you about the house. A quick stop for lunch and then it was up to our final place of rest. Perched high above the city, Case Study House #22 is not only one of Koenig's finest works, but also one of Los Angeles' favorite sons. In as much as the city makes the house, the house also sort of made the city. By far the stand out icon for Mid Century Modern and more importantly SoCal Modern design, the rigors of Koenig's hands and Schulman's eyes helped make Southern California and Los Angeles as the posterchild for life lived as it should be. The original and still current owners, the Stahl family, graciously allowed our small gang of bicycle bandits to gaze at the city from a perspective that very few do. We posed like the two women in the photo, conjured images of 60s LA, and reminisced about all the history and fun the house has laid witness to. Its a stunning home, an incredible site, and an experience like none other.

A Case of Koenig Modern Photos

Sunday, March 8, 2009

The King of California Modern...

Our next endeavor into the Case Study world brings us up above Sunset and into the Hollywood hills to grab unparalleled views from behind the steel-glass minimal designs of SoCal modern pioneer Pierre Koenig. We'll return to the Palisades to start the ride to visit one of Koenig's later works,the Schwartz residence, followed by Koenig's own second residence in Brentwood where his family still resides. From there, we'll make the long trip up to the hills where we'll see Case Study House #22, also known as 'The Stahl House', and Case Study House #21, which is known as the Bailey House. Both Case Study homes have been recently restored, and are in immaculate condition, and on this occassion we get to see one of them from a perspective that very few ever have. Tour begins on the westside @ 10:30 at Clover Park in Santa Monica, and will finish up in the hills with a 4pm tour of CSH #22. Stahl House tour is $20, so dont forget to bring cash! See everyone Saturday.

The Minimalist M.O...

Case Study Series Part Deux. As we moved east from our start in the Palisades a few weeks earlier, we found ourselves searching for the Case Study gems in even more obscure but somehow just as beautiful locations. This go 'round would celebrate the brilliance of Craig Ellwood's minimal as modern m.o., which brought us high above the city at the end of a nearly 600 ft climb atop Bel Air. Not exactly the kind of thing that brings a grin to your face (at least this time there were no naive promises as to when the climb might end).

CSH #16 is the first of three homes Ellwood produced for Entenza and his Case Study Program, and, unfortunately, the only surviving project Ellwood has to show for his efforts. But it is brilliant, make no mistake about it. His earlier works combine the prefab language inherent to Eames' work and the diagrammatic wizardry of Neutra's later designs. This is that combination at its best. Take a gander at the floor plan, and its almost indecipherable. You'll see tile patterns, furniture and a fireplace, but where are all the walls?!?! To Ellwood's credit, there really aren't any. Except for a few key points where he lets the vertical grace the horizontal, the house appears to be a thin plane floating above a ribbon of glass waving in and out of the structure. And perhaps this is why Entenza liked him so much.

For Entenza's own home, Case Study #9, he commissioned Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen to deliver him the ultimate pre-fab bachelor pad. Entenza was a big fan, to say the least, of steel prefab construction and the enormous potential it had for delivering efficient, affordable, off-the-shelf designs. But what he liked most about it, was the ability to generate space with minimal structure, and unlike Eames who sought to express the structure in his designs, Entenza would rather reep the spatial benefits than ebellish the detail.

Enter Ellwood.

Ellwood had no formal architectural training. In fact, his understanding of the profession, and ultimately the source of his control over it, comes from his time spent working with developers and contractors. He noticed that the number one way to see a project fall flat was to add too much 'architecture to it. His approach, rather, sought (in keeping with Mies' notion that 'god is in the details') to utilize the minimal amount of materials, but to put the utmost care and consideration into how those materials come together. Nowhere is this more apparent than in CSH #16. Going back to the question of structure in the home, he utilizes the roof plane as a space to hide structure so that the beams only appear in a shadow line detail as they course across the house and touch down at a column, where he directs the vertical loads. As for the lateral loads, Ellwood cleverly and strategically places a few solid walls in the house which double as privacy screens, garage edge, and a fire place. All while preventing the structure from torquing on itself.

The result is amazing. Neutra's notion of exterior as interior, Eames' notion of carefully assembled off-the shelf- components, and Entenza's love of open space. All in one place. With views of everywhere else.

A Case of Ellwood Modern Photos

Friday, March 6, 2009

In Mid-Century Modern We Trust...

'A Chautauqua by the Shore' was to be the ride that kicked off our Case Study Homes rides; rides celebrating the homes that had been selected to be a part of Art & Architecture Magazine's 'Case Study Program' during the late 1940s and 50s. And it was. And it did. The ride took us to a valley in the Palisades which is home to four Case Study Homes, and what's more is that they're all nestled together on the same bluff overlooking the Pacific (well, minus that one lavish obstacle obscuring CSH #9's view, but there's hope that thing may slide off the hillside soon enough). Eames, Neutra, Saarinen, and Walker all produced some of their best work here, and they're all accessible by a single driveway. Breakthroughs in pre-fab technologies, furiture design, and what we now call 'sustainable/eco friendly/environmental/and whatever other buzzwords you can conjure up as a prefix-design' all landed on one spot. And, oddly enough, it seemed like the overall reaction paled in comparison to a pitstop we made in Venice to visit a bunch of trailer sized bungalows by some second rate, err, second generation architect...who couldn't even get into the exclusive Case Study club (damn communists!).

Before our epiphany inducing landing in the Palisades, we made a quick stop to visit one of the country's earliest 'modernique' developments. Designed and built from 1948-1952, Gregory Ain's Mar Vista tract in Venice is not only one of the earliest modern developments, but also probably the one which best embodies the modern spirit. Yes it has big expanses of glass. Yes it has roof planes that extend outward in a diagrammatic fashion. Yes it has off the shelf components used as architectural elements (even a car headlamp harking back to one of Ain's mentor's earlier works). But what it does have, makes up for what it doesn't have, and that's a lot of space. But the lack of space is actually the most endearing part of this project.

Each original home measured only 1060 sq ft in total (excluding the garage), but like other great modernists, Ain was a brilliant organizer of space. Enter the home, any home, and you start in the kitchen essentially; move to the living room, followed by the dining room, and the bedrooms are off down a corridor. Pretty typical. Except that Ain recognized that not all families are alike, and that the gift of flexibility is a gift that keeps on giving. Look closely and it becomes apparent that the kitchen and the living room are more or less one space semi-privatized by some shelves, and maybe a venetian blind or two. And the bedrooms. The bedrooms could be plural, but slide a few walls around (literally, they slide) and they become one larger room open to the house, unless the wall to the dining room has been slid into a closed position. And I guess its kind or difficult to really call it a living room. There are couches and a fireplace, but next to the fire place is a glazed wall with a door to the porch which makes the living room really just the softer side of the porch. Nothing is really defined as a static space, so the home feels larger than the numbers suggest, and I think thats what made it so relevant.

Given the state of the economy and an ever growing presence of mind about our individual impacts upon the earth (not to mention the impact we'll leave as a culture and a civilization), the idea that such a small building footprint could actually be an incredibly comfortable place to live is pretty reassuring. Overhearing how great it felt to be in such a cozy space, or 'man, i grew up in something 3 times as big, and that just feels like a total waste of space', or how the cliched criticism of modernism as being starck and austere seems to make absolutely no sense at all, is just something I'm glad I got to be a part of. In a time of gloom and doom, the notion that we have one saving grace on the horizon, seems to, if for nothing else, at least leave us with a little hope.

A Chautauqua by the Shore Photos

Sunday, January 18, 2009

Hurts So Good...

The rides succeeding the first Frank Lloyd Wright tour took us to some of the most important locations of modern architecture in Los Angeles. Visiting R.M Schindler's bohemian campsite in West Hollywood, Leonard Malin's Chemosphere in the Hollywood Hills, and George Sturges' cantilevered Usonian in Brentwood was a pleasure to say the least. Stunning works that helped define the concept of 'California Modern', questioned our notion of how a building engages its site, and what 'American' architecture is, and consequently has the opportunity to be. The homes were awesome. The rides, though, are where formality is forgotten, and the bickering begins.

The rides were awful. Well, at least they hurt. A lot. And that we're not going to debate. And that's the point.

Covering the final works of Frank Lloyd Wright took us from Silver Lake all the way to Rodeo Drive (I know, I would never have expected to see Wright on Rodeo, but hes there, trust me), and eventually over to Brentwood to visit said Usonian wonder. It was doable ride except for a quick climb up to visit Lautner's Wolff Residence perched above the Sunset Strip. Most of the stops were relatively low lying and not too far off the beaten path. That is, unless you make a wrong turn and find yourself in a bamboo grove staring eye to eye with something that looks like a cross between Stonehenge and a shoji temple. A shoji templed which Schindler himself used to live in.

Everything is hand crafted. Everything. Site cast concrete formed by burlap give the tapered walls that enclose the main living spaces a texture that is like a fluid in suspended animation. The timber framing that fills out the remaining elevations dances along the house like a ribbon whipping in the wind. Each vertical break in the strand defines both itself and an opportunity to continue the logic of the form along another plane; a plane which opens to the courtyard like a tent that opens to a campsite. There's even a hammock, except in this case, it's in the trees, not hanging between the base of two of them. Vacated of all furniture and personal belongings, the house remains merely a shell, but in so being, it becomes more than a series of well composed architectural elements. The Schindler House in its present form represents the strength and power of the diagram in how it can inform architecture. Stunning.

Skip ahead another ten miles; the odometer clicks 20, and you're looking forward to one brief stop before returning to the east side, there's one last climb. 'One last climb'. Ha. Don't believe it when you hear it. That last stretch up into the Brentwood hills to see the only Usonian house in Los Angeles is a rough one. Your legs will be jelly. You will be out of breath. And, at the time, you will hate having agreed to doing this. But when you get to the top of Skyeway Road, and you're hallucinating from the lack of oxygen, its all worth it. And that's the point.

Wright's house for George Sturges is Los Angeles' only Usonian home. And it fits the bill nicely. Typical to the Usonian parti, the house makes use of native elements like redwood and brick, utilizes verandas and generous overhangs to take in views while making use of passive cooling strategies, and maintains a relatively modest footprint. The most unique aspect about this Usonian in particular, though, is the way it approaches the site (not a big surprise given that Lautner was the associate in charge of the design at the time). The house seems to be a ship cresting over the top of a twenty foot wave, only its hull is is a frighteningly cantilevered patio sitting above a brick faced retaining wall which seems to slice through the home as it forms the chimney above. The view from the patio is amazing though. On a clear winter's day, all of LA, whitecaps in the background to boot, is visible. Its at this point that the climb, the pain, and the slight disorientation is well worth it. Leave the bickering for later, this is about as good as it gets. Well, almost.

The next ride we collectively termed 'Broken Legs, Hot Homes' for a reason, and its not one that needs a lengthy explanation.

Los Angeles is a city intimately linked to its topography. Some of the best spaces and structures can only be found after you find yourself at the end of a steep ascent, or the bottom of a canyon road looking out into the Pacific. Unfortunately, the best architecture seems to be included in the former. Strictly. 'Broken Legs' took us up to Mulholland to visit a study of the minimalist case in Pierre Koenig's Bailey House, a tree house for Ellen Jansen (and R.M Schindler, but don't tell anyone you know), and Lautner's masterpiece floating up in the clouds above the San Fernando Valley.

These homes are astonishing. Just like the last ride. After the uphill battle is over, there's only 'one last climb'. Just like the last ride. And the ride is awful...but way worse than the last ride.

The ride by the crow's wings is no more than 10 miles 'a to b', but it just never seems to stop going up. The first stop at Schindler's Jansen Residence, is, in theory, 90% of the climb, seated essentially at the foot of Mulholland Drive, but the climb to Koenig's Bailey House makes that 10% seem pretty significant. Thankfully, though, the simplicity of the Bailey House can smooth over any anxious tendencies with just a few strokes of the brush. Situated atop a pristine and uncharacteristically level site, the house, with a modest square footage of not much more than 1000sf, is one of Koenig's earlier examples of what has come to define California Mid-Century Modern. Clean crisp lines, large expanses of glass with views to the horizon, and attention to even the most minute detail.

Before our final stop, we take a detour to visit a Lautner masterpiece with an unexpectedly unfriendly owner, and then its off to a house that is both 'of heaven and earth' and neither at the same time. Oh yeah, and one more climb. I swear.

Lautner's Chemosphere is that 'almost'. Perched above Mulholland Drive and overlooking the entire San Fernando Valley, the Chemosphere is the ultimate examples of architecture's attempt to reconcile its impact on the earth. A veritable flying saucer hovering over what had, at one point, been deemed and unbuildable slope, the house is modest octagonal single story residence resting on top of a single concrete column. Views every which way, and approachable only by a sky bridge, which is, in turn, only approachable by a funicular. There really is nothing like it. Not even close. So theres only one thing to do. Throw caution to Benedikt Taschen's wind, and climb the slope to look over what Chemosphere looks over. The view is amazing, but the most interesting thing about being up close and personal with the house and the views that it affords is the relationship that you then form with it. Viewed from below, the house reads mostly from its underbelly (and one whose texture is actually kind of similar to the texture of Sturges' wood fascia cantilever), but from above the house takes on a completely different personality. The glazing on each of sides of the octagon are split by the laminar beams supporting the roof which give them the appearance of being more like eyes on one of the house's many faces. So you sit and stare. And Chemosphere stares back. You nod in a kind of quiet appreciation to what Chemosphere has let you see and be a part of. Then you lay back against the hillside and gaze off into the distance, and that ride up that had you swearing to the heavens leaves you there, without a care in the world. And thats the point.

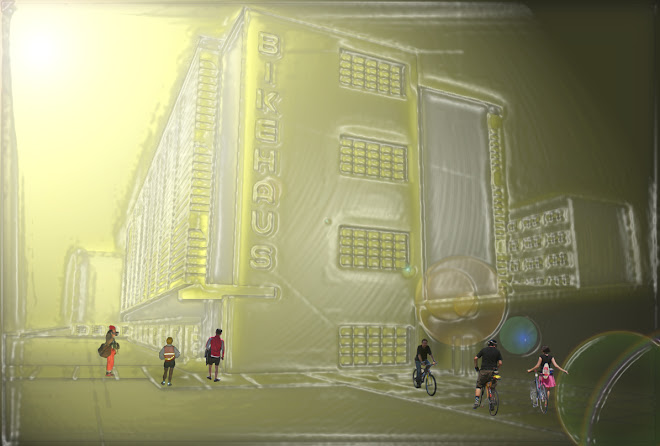

BikeHaus seeks to open a dialogue generated by an appreciation for great design, a sensitivity to our surroundings, and a willingness to share out own thoughts and feelings by engaging the wonders of modern architecture in Los Angeles one ride at a time. The rides are rarely a breeze. To a degree this is unavoidable. Los Angeles is hilly. But, it is also intentional. Theres nothing quite like gasping for air and cringing with each new step, only to look up and be completely blown away. We love great architecture, but why not use it as an excuse to go for a good ride?